Life After Chase: Gail Buyske

Life After Chase: Gail Buyske

A Personal Perestroika

Chase alumna Gail Buyske addressed The Microfinance Club of New York on July 31, 2008 on the topic of Russian microfinance/sme lending.

Her presentation was based on the six years she spent as chairman of the board of a Russian microfinance/sme bank, about which she wrote a book that published in 2007 by Cornell University Press. A lot of her experience, she says, involved reconciling her Chase experience with Russian "reality."

We asked Gail to write about her "life after Chase".

I left Chase in 1991 after 12 wonderfully varied years that included assignments in Loan Work-Out, Chase Hong Kong, Western Hemisphere Credit, Trade Finance and the Soviet and Eastern European Division. Ironically, my departure was precipitated by the once-in-a-lifetime experience I had in the Soviet and Eastern European Division during perestroika. Chase’s dominant position in that market gave me the opportunity to work closely with a memorable group of people (including Frank Stankard, Bob Weiss, Bob Bublitz, Barbara Samuels, John Minneman and John Charlton) to evaluate possible future strategies for the bank. It also forced me, however, to realize that the most intriguing opportunities – and risks – in the region weren’t suitable for Chase. Having been fascinated by Russia ever since my first encounter with the Cyrillic alphabet in college, I exercised my own perestroika by leaving Chase to immerse myself in this rapidly changing world.

From 1991-98, I worked as a banking consultant while completing a PhD in political science at Columbia University. Consulting gave me the opportunity to work on banking issues from a variety of angles, ranging from helping a Chinese bank create a loan rating system to analyzing financial sector development in the former Soviet countries. Although I had expected that a PhD would take me into the lofty thinking of an academic career, I found that I was most interested in linking the theoretical and the practical. Therefore my dissertation research on the development of financial systems in post-socialist economies was an attempt to place banking – not a typical interest of political scientists – into the academic framework of political power and state capacity.

Consulting in emerging economies was enormously fun and gratifying through much of the 1990s, because I realized that so much that I had taken for granted at Chase was exactly what my clients needed: a strong and open credit culture, clear lines of responsibility, logical and consistent credit analysis, and good reporting systems. The most fascinating part of the challenge wasn’t identifying what my clients needed, but figuring out how to help them identify these needs themselves. Sometimes I felt like an amateur psychologist. One of my favorite experiences, to this day, is describing the old Chase risk rating system to bankers; they are always impressed when I tell them that a risk rating 4 meant the same thing to Chase bankers from Africa to Asia to 1 Chase Plaza. I’m impressed too when I think about it now; having seen a number of dysfunctional corporate cultures, I am better able to appreciate how factors like the risk rating system underpinned the strength of Chase’s corporate culture.

In facing the challenge of how outsiders could make a signficant contribution to banking sector development, I became interested in corporate governance and particularly the differences that an equity investor could make by exercising leverage as a shareholder. This line of thinking put the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) on my radar screen, where I was delighted to learn that Kurt Geiger was responsible for the EBRD’s Financial Institutions Group. Kurt helped me fulfill a lifetime dream by sending me to Moscow, where I spent three years as the senior member of the Financial Institutions team. My timing couldn’t have been better; there was absolutely no competition when I arrived in Moscow six weeks after Russia’s 1998 financial crisis! The EBRD had been created to take exactly the kinds of risks that Chase wasn’t able to take when I left in 1991, so I felt as if I had gone to professional heaven. The fact that David Klingensmith and Bob Harada were in the EBRD’s credit department contributed to my EBRD experience; being able to speak a common banking language with them and Kurt was an oasis of understanding in a still young institution grappling with a huge range of national cultures and professional backgrounds.

In facing the challenge of how outsiders could make a signficant contribution to banking sector development, I became interested in corporate governance and particularly the differences that an equity investor could make by exercising leverage as a shareholder. This line of thinking put the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) on my radar screen, where I was delighted to learn that Kurt Geiger was responsible for the EBRD’s Financial Institutions Group. Kurt helped me fulfill a lifetime dream by sending me to Moscow, where I spent three years as the senior member of the Financial Institutions team. My timing couldn’t have been better; there was absolutely no competition when I arrived in Moscow six weeks after Russia’s 1998 financial crisis! The EBRD had been created to take exactly the kinds of risks that Chase wasn’t able to take when I left in 1991, so I felt as if I had gone to professional heaven. The fact that David Klingensmith and Bob Harada were in the EBRD’s credit department contributed to my EBRD experience; being able to speak a common banking language with them and Kurt was an oasis of understanding in a still young institution grappling with a huge range of national cultures and professional backgrounds.

The EBRD also introduced me – kicking and screaming – to the world of microfinance. When I was asked in 1999 to join the board of directors of a micro and small business bank (KMB) being created by the EBRD, I thought it was one of the worst ideas I had ever contemplated. Not only had I learned about the challenges of middle market customers while I was at Chase, but my consulting work had made it clear that many Russian banks had found ways to make money that didn’t involve lending.

My reluctant agreement to join the board for a short period (I was thinking of 3-6 months), led to my becoming chairman of the board for a period of six years, until majority ownership of the bank (KMB) was sold to Banca Intesa. This completely unexpected and ultimately exhilirating experience forced me to re-think what I thought I knew about lending to small entrepreneurs as well as about the potential growth of Russia’s middle class. It also made me conclude that microfinance’s self-assigned label as an anti-poverty tool actually restricts its application; microfinance is really just good banking applied to a class of borrowers that bankers hadn’t realized were creditworthy. I wrote Banking on Small Business: Microfinance in Contemporary Russia as a way to share hard-learned lessons that I consider important for economic development.

I returned to consulting after leaving Russia in 2001 and have been gradually allocating more time to corporate governance work. I’m currently a non-executive director of Swedbank, which has operations in several former Soviet countries, as well as the EBRD nominee director at Kazkommertsbank (the largest privately owned bank in the former Soviet Union) and URSA Bank, a large Russian bank. I’m frequently reminded of my first encounter with Chase; during my interview with Frank Shea in 1979, he told me that he often returned to the principles of the Chase training program when he had to work through a problem. Not only do I continue to rely on those principles, but I still have my files in the basement!

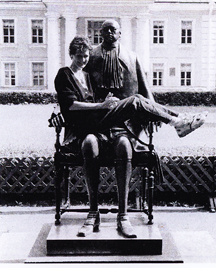

Photo above: Gail in the arms of Peter the Great