Ulises Giberga: Reminiscences of Chase Cuba

Tales of Half-Truths...and Che Guevara

After David Rockefeller died, Chase alumnus Ulises Giberga wrote a tribute for the CAA website noting, "David will be remembered for the many good things he did in life, and I will always remember him especially for one little-known position he took back in 1960. Chase Manhattan branches in Cuba had been nationalized by the Castro government in September 1960, with no compensation offered. There were more than 20 Cuban-born employees, I among them, working in the Cuban branches, who had been recognized as having served exceptionally well, and had expressed no desire to continue living under the Castro dictatorship. While David was not on Chase’s Board of Directors at that time, he was most instrumental in arranging for senior management to approve Chase’s re-hiring those of us who left Cuba in New York and other locations. It was David’s strong hope that things in Cuba would settle down and that Chase would soon be able to re-open its four branches there. Alas, this was not to happen. So, thank you, David, on behalf of all of Chase’s Cuban employees."

CAA asked Giberga if he would send under reminiscences of Chase Cuba and those fateful days in 1960. He sent these vignettes:

♦ When it became clear in the summer of 1960 that, given the bitter acrimony between the United States and the Castro government, Chase and the other American banks with Cuban branches (Citibank and First National Bank of Boston) were at high risk of being intervened or nationalized, Chase decided to bring back to the United States as many of the American staff and their families as possible. Our Vice President in charge of the Cuban branches, Tom Findlay, and his wife were to stay in Cuba. Also asked to stay to help Tom Findlay was a young Assistant Treasurer, Otto Reisman, but his wife, Anne, was told to go to Miami with the other expatriates (among them, Bill Beaulieu, Frank Brennan, Tom Carter, Jerry Schneiderman and George Malcolm, and their families). The Reismans were a very impressive couple. Otto was a large man, probably 6’5”, with a Germanic appearance that somehow made him seem menacing, and Anne was a tall woman, maybe 6’2”. They were both very charming and well-liked. I remember the day when all the Cuban and American officers were told about the repatriation plan. Bill Beaulieu described the specifics, and I was standing next to Otto. Otto stood up very straight and said to Bill, “Well, I guess I’m just indispensable.” Bill replied, laughing, without taking a breath, “No, Otto. You’re just expendable”.

Below: Castro signs laws to nationalize U.S. banks in Cuba. (AP Photo)

♦ On Sept. 17, 1960, the Cuban government enacted a law that ordered the nationalization of the American banks, including Chase. The Bank of China, which was being run by a group loyal to Taiwan, was forced to change its management to a pro-Communist China group. The Canadian banks (Royal Bank and Scotia) were left untouched, as were the Cuban banks, which were nationalized some weeks later. I had already decided long before that I would leave Cuba when this happened and hope that the United States would intervene in Cuba and somehow get rid of the Castro government, so I started planning my exit. I had a month’s vacation coming and thought this would allow me the opportunity to get out.

While for a long time all that you needed to exit Cuba was a valid passport and a visa to whatever country you wanted to visit, the Castro government had put in a new requirement: You needed an exit permit. My travel agent sent me to the police station in my neighborhood to apply for the permit, where I was told that since I worked for a bank that had been nationalized, I needed the approval of the government “interventor”.

I went back to the bank and told the interventor (a pleasant young man, Manuel Taboada, who had been a clerk in our Loan Department a couple of years earlier and had left Chase to join Banco Nacional de Cuba, the central bank) that I had a month’s vacation coming, was very tired and needed a rest, and that friends in the United States had offered to pay for my trip and stay in New York. I said I’d be back in a month. Taboada said, “No problem. Draft a letter to the police authorizing your trip, and I’ll sign it. But do me a favor: When you return, bring me back a pack of Gillette Blue Blade razor blades. I can’t find any in all Havana, and I don’t like what little they have.” I replied, “Gladly, will do, thanks!”

Towards the end of October I wrote Taboada from New York, telling him that I was very nervous and feeling poorly and asked for a three-month leave of absence. A few days later I received a reply on Chase stationery to which had been added the word “Nationalized”, saying that if I was not at my desk by Nov. 4, 1960, I could consider myself “fired”. So I accepted the fact that I was fired by the nationalized Chase-Cuba and resumed my career with Chase-New York.

Now, fast forward to 1989. I had retired from Chase on December 31, 1989 and two months later joined Republic National Bank of New York, where i was appointed Senior Vice President and General Manager of International Private Banking Latin America (ex Brazil).

Early in 1989 I made my first trip to Uruguay, where Republic had a representative office headed by Alberto Fabius. When Alberto found out that I was a Cuban, he told me that he had a Cuban friend who had worked for a time in Uruguay and was now working in an Israeli bank in New York. His name? You guessed it: Manuel Taboada. When I returned to New York. I called Taboada. We had a delightful lunch together, and I gave him a little pack of Gillette Blue Blades.

♦ Leaving Castro’s Cuba was not a pleasant event. For many months the government had found ways to harass and annoy any Cubans who objected to the country’s move towards Communism. For example, if you made a phone call and the other party didn’t answer after three or four rings, a recorded voice would start reciting revolutionary slogans, like With or without the OAS, we will win the battle. So we asked all our friends to please answer the phone as soon as it rang. Any Cuban who left the country was labeled a “gusano” (worm). While waiting at the airport for a flight to Miami to start boarding, you were ushered into a glass-enclosed room referred to as “the fish bowl”, where loud-speakers constantly repeated revolutionary slogans and references to “you worms”. Even after you boarded the plane, you were not guaranteed departure. The authorities, almost on a daily basis, would instruct the pilot to open the cabin door, and two soldiers would march in and point to a passenger and say, “You. Come with us. You’re not leaving today”.

On Oct. 4, 1960, I took a Pan Am flight to Miami with only a five dollar bill in my pocket. I was met in Miami by Bill Beaulieu, who welcomed me to the United States and assured me that I had a job in Chase New York waiting for me. I spent three days in Miami with relatives and friends who had already left Cuba, and flew to New York to rejoin the bank.

While I had really believed that I would be back in Cuba just a few months after I left, I didn’t actually get to return until 2010, 50 years later. By then Cubans who returned to Cuba were no longer referred to as “worms”; we were now called “butterflies”. The reason: Cuba needed foreign exchange, and Cubans returning as tourists provided the U.S. dollars, so we were supposedly welcomed back. Actually at least I was not exactly welcomed back, but that’s another story.

♦ I have been back to Cuba twice: the first time was in February 2010, roughly 50 years after I’d left. When my wife Jane and I returned to New York, I announced that there was no need for me to ever return to Cuba, as I had taken care of any “loose ends” remaining. In late 2015, however, our oldest grandson, Jack, who was 10 at the time, wrote a short essay on Cuba that impressed me greatly. I started to think that I really owed it to my children and grandchildren to share with them my memories of what it was like to grow up in Cuba and to show them what Cuba was like now. So in July 2016, Jane and I took our children Susana, Peter and his wife Samantha, and Elena and her son Jack to Havana on a week’s vacation. Elena’s husband, Bob Tompkins, didn’t come because he had to stay with daughter Katie, who, like Peter’s three children, was then too young to make the trip.

Chase National Bank of the City of New York, as it was known then, had been in Cuba since the 1920s, when it acquired local banks. When I joined it in 1953 as a Credit Analyst, after graduating from Brown University in June, Chase had four branches in Cuba: the main office in downtown Havana’s business district (Aguiar 310 between Obispo and O’Reilly streets), and smaller branches on Amistad Street (in Havana's fancy shopping area), on 23rd Street in Vedado, an upper-middle-class residential area (see photo above), and in Marianao, a middle-sized town not too far from Havana. Chase was known primarily for financing a large percentage of Cuba’s sugar crop; it was still smaller in deposit size than its two American rivals, National City Bank and First National Bank of Boston. The three U.S. banks were also smaller than their Canadian counterparts (Royal and Nova Scotia), but the biggest banks were those owned by native Cuban investors (Trust Company of Cuba, Banco Continental Cubano, and many others).

Chase National Bank of the City of New York, as it was known then, had been in Cuba since the 1920s, when it acquired local banks. When I joined it in 1953 as a Credit Analyst, after graduating from Brown University in June, Chase had four branches in Cuba: the main office in downtown Havana’s business district (Aguiar 310 between Obispo and O’Reilly streets), and smaller branches on Amistad Street (in Havana's fancy shopping area), on 23rd Street in Vedado, an upper-middle-class residential area (see photo above), and in Marianao, a middle-sized town not too far from Havana. Chase was known primarily for financing a large percentage of Cuba’s sugar crop; it was still smaller in deposit size than its two American rivals, National City Bank and First National Bank of Boston. The three U.S. banks were also smaller than their Canadian counterparts (Royal and Nova Scotia), but the biggest banks were those owned by native Cuban investors (Trust Company of Cuba, Banco Continental Cubano, and many others).

I think the entire Cuban banking system had been nationalized by 1961, and when I returned in 2010 I was very curious to see what was left of Chase. This is what I wrote in my diary when I came back in 2010:

“We took a photo of the outside of the building and walked inside. I thought we were in a time warp. The customer platform, on both sides of the steps leading inside, seemed unchanged, and I could see the tellers’ cages and what used to be the Exchange Department in the distance. We were of course stopped and asked what we wanted, which was to walk around and go upstairs. The expected answer came back: “No!”. My cousin’s daughter, Alina, asked if she could talk to the manager; they spoke briefly on the phone, and the manager, a youngish not particularly friendly woman, came to see us. Alina explained who I was, and the manager, sullenly, said she’d accompany me (just me) to the second floor. “No photos!” The elevator, I swear, was the same one I had ridden in 50 years earlier.

The second floor had consisted, on the right, of two private offices (for Tom Findlay, the VP, and Guillermo Carreras, the AVP) and a conference room in the middle. On the left was an open working area with maybe 30+ desks and file cabinets; this area (where I had worked) was now enclosed and not to be viewed. The doors to the two private offices were closed, but the door to the conference room was open, and to my surprise I noticed that the floor tiles were exactly as I had remembered! Then I looked at the glass door to Mr. Carreras’ old office and to my further surprise saw the engraved initials CNB. Chase had been known as The Chase National Bank of the City of New York (CNB) until 1955, when it merged with Bank of Manhattan and became The Chase Manhattan Bank. We had never bothered to change the lettering from CNB to CMB, and obviously neither had the government. Quite a revelation.”

On our trip last year, I was hoping to visit the bank again, but we went a bit late on a brutally hot Saturday, and the bank had already closed for the day. A very polite guard asked us to come back on Monday, but we were unable to.

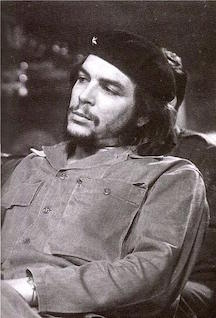

♦ A day or so after the foreign banks were nationalized, one of Chase’s security guards, Manuel Carro, told Tom Findlay, the VP, that he had overheard some of Chase’s more rabid employees talking about their plan to raid Tom’s house that night. Tom was also a director of Cuba’s central bank, Banco Nacional de Cuba, which at that time was headed by Che Guevara. Tom phoned Che and reported the conversation; Che replied that, on his word of honor, nothing would happen and he would be safe. Nothing did happen, but to be on the safe side, the Findlays and Mr. Carro left Cuba the next day.

♦ A day or so after the foreign banks were nationalized, one of Chase’s security guards, Manuel Carro, told Tom Findlay, the VP, that he had overheard some of Chase’s more rabid employees talking about their plan to raid Tom’s house that night. Tom was also a director of Cuba’s central bank, Banco Nacional de Cuba, which at that time was headed by Che Guevara. Tom phoned Che and reported the conversation; Che replied that, on his word of honor, nothing would happen and he would be safe. Nothing did happen, but to be on the safe side, the Findlays and Mr. Carro left Cuba the next day.

Mr. Carro was one of the 20+ Cuban employees of Chase-Havana who were offered jobs in Chase-NY as recognition of their past services to the bank or their future potential. (In the case of Mr. Carro, it was at a considerable risk to his personal safety.)

While not everyone in New York agreed with this policy for fear that it would create a precedent that might not be welcomed years later (remember, this was 1960, a very different country from what it is today), it was David Rockefeller, not then yet a member of Chase's Board of Directors, who convinced the bank that this was the proper path to follow. I don’t think there are any regrets.

About Ulises Giberga

Ulises Giberga was born in December 1932 in Havana, Cuba, where he attended grade school before enrolling in the Peddie School, Hightstown, NJ. He graduated magna cum laude from Brown University in 1953, with a BA in Economics. He minored in math and French and was a member of Phi Beta Kappa.

While at Brown, he attended the University of Havana Summer School and earned a Cuban Government Certificate for Teaching English as a Foreign Language.

On June 29, 1953, Giberga joined Chase, Havana in the Credit Deparment. He was sent to New York in January 1954 for credit training and was appointed Assistant Manager of the Cuba branch in 1956/57. He also attended the University of Havana Night School during periods of 1954 to 1957 and completed three out of the five years required for a CPA degree but was unable to finish when the University was closed due to political unrest.

The Chase Cuban branch was nationalized on Sept. 17, 1960. Giberga was hired by Chase New York on Oct. 10, 1960, to work in the Caribbean Area office in New York.

Later posts included: Nassau, Bahamas, as Secretary/Treasurer of The Chase Manhattan Trust Corporation Limited; Charlotte Amalie, St. Thomas Virgin Islands branches as Assistant Manager, head of Credit Department; St. Thomas as Assistant General Manager for Branches in Northern Caribbean (ex Puerto Rico); Miami as VP CMOC-Miami and General Manager of Chase’s branches in the Caribbean (ex Puerto Rico); New York as Head of Western Hemisphere Correspondent Banking and General Manager of Private Banking International- Western Hemisphere. He retired from Chase at the end of 1987.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

COMMENTS

From Dra Marlene Llópiz: My father, Gustavo J. Llópiz–a 35-year veteran at Chase in Cuba, New York and Mexico–worked at Chase starting as an office boy in Cuba, moving to New York to flee Castro (again working at Chase). He transferred to Mexico City in 1970. His career ended abruptly on May 3, 1983 when he died at 53 from a ruptured aortic aneurysm. At the time he was Senior VP at Chase in Mexico City.