and John Quincy Adams (1767-1848):

or fairness as understood by the American government.

10. Adams’s return to The Hague: the Bourne Ultimatum

This arrangement with Sylvanus Bourne was in reality an ultimatum to the Treasury. On December 12, 1796, Adams ordered Samuel Meredith (left) (1741-1817), Treasurer of the United States of America (not to be confused with the Secretary), that he had accepted a letter of exchange (the first of a series of four) of USD 16,000. This amount was for value received by Adams for the use of the United States from Sylvanus Bourne. The draft had to be paid at 60 days sight to Sylvanus Bourne or his order. Once the draft was presented, the clock started ticking. If the draft weren’t paid after 60 days, it would be protested. Again, it was an ultimatum, but a smart one.

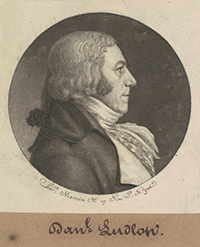

This arrangement with Sylvanus Bourne was in reality an ultimatum to the Treasury. On December 12, 1796, Adams ordered Samuel Meredith (left) (1741-1817), Treasurer of the United States of America (not to be confused with the Secretary), that he had accepted a letter of exchange (the first of a series of four) of USD 16,000. This amount was for value received by Adams for the use of the United States from Sylvanus Bourne. The draft had to be paid at 60 days sight to Sylvanus Bourne or his order. Once the draft was presented, the clock started ticking. If the draft weren’t paid after 60 days, it would be protested. Again, it was an ultimatum, but a smart one. bankers in Amsterdam, was the firm where Daniel Ludlow (right) (1750-1844) learned his profession as a banker in the period 1765-1770. Through his mother Elisabeth Ludlow (née Crommelin), he was related to the family.

bankers in Amsterdam, was the firm where Daniel Ludlow (right) (1750-1844) learned his profession as a banker in the period 1765-1770. Through his mother Elisabeth Ludlow (née Crommelin), he was related to the family.11. Incidents leading to Adams’s loss of confidence in De Wolf

De Wolf started the collection process immediately after receiving Adams’s authorization. He was authorized to draw up to 49,700 Dutch guilders on the House of Crommelin. But to pay his investors, he needed Brabantine guilders in cash money and not Dutch guilders (draft). His position was long Dutch guilders (draft) and short Brabantine guilders cash. To find the Brabantine guilders cash, De Wolf had to find traders/merchants in the market who were in the opposite situation: long cash Brabantine guilders and short Dutch guilders (draft). When the exchange rate was agreed upon between the parties/market, the traders drew drafts in Dutch guilders on De Wolf (who accepted) and paid him Brabantine guilders in cash. De Wolf thus received the cash required to pay the interest to the bondholders. To complete the transaction, De Wolf then drew drafts in Dutch guilders on Crommelin and Sons with the names of the beneficiaries. They were paid Dutch guilders in cash or with a draft. This completed the cycle for the first payment.

hen Adams got the account statement, he was flabbergasted by the costs of exchanging Dutch guilders for Brabantine guilders. He wrote to De Wolf that the transaction costs amounted to 3.5 percent – bad news because a second payment of roughly the same amount still had to be performed. Adams requested De Wolf to propose solutions to bring these costs down. On December 13, 1796 he wrote, ”As I have undertaken this transaction at my own discretion and solely for the purpose of preventing any delay in your payment that could by any possibility be avoided, I request this information of you in order to serve as my justification for taking the extraordinary step to raise money, and I hope that you and the creditors will perceive it as a new proof of the fidelity of the United States in the performance of all their engagements.”

Adams was very depressed for personal as well as professional reasons but also because of the bad tidings about the political situation in the United States. He had taken great personal risks to secure payment of part of the interest. Based on the correspondence, it is obvious that De Wolf wasn’t aware of Adams’s situation. On December 19, 1796, De Wolf wrote that transaction costs for the payment of the next interest tranche could exceed 6 percent. He gave a very logical technical explanation: The King of Sweden had given notice that he would redeem the Swedish loan and that repayment of a large amount in foreign currency would increase the demand for Brabantine guilders – and hence the exchange rate. De Wolf also renewed his interest in arranging a loan for the United States in Antwerp. Judging by his response, Adams misunderstood De Wolf’s proposal as a sort of blackmail: lower costs for more American business.

Adams’s modus operandi had, temporarily, shifted from analytical and patient to anxious and agitated. He desperately needed good news and De Wolf was the bearer of more bad news. To make the perception worse, De Wolf’s letter of the 19th arrived in The Hague at the same time as his letter of December 16, 1796, referring to a letter from a New Yorker in The Rotterdam Gazette describing the turmoil in the United States: “The people there [in New York] were very fearful that with reference to the election of the new President, the Provinces were divided amongst them and that it was even apprehended that a separation between the South and North States might ensue and of course the people begin to fear for their stock if such an event happened. Pray Sir please to tell me whether any intelligence came from America and if the election of the New President can have any the like consequences, if so it would be devastating for the credit.”

Not De Wolf’s best English but with the benefit of hindsight we know that the news in The Rotterdam Gazette was factually right. From Adams’s perspective, it was an absolute horror scenario that, based on his information, could not be excluded. This was probably also the moment that he lost his previous “sympathy” for De Wolf as the underdog banker versus Willink and Staphorst as the lead bank of the United States.

Adams’s reply is dated December 22, 1796. The letter treats several subjects that are classified in an ascending order of importance. The style also changed from technical and calm to rather aggressive. Adams declined De Wolf’s offers with regard to the financing of the second tranche of the interest as well as concerning “a” reduction in the transaction costs/exchange rate. Adams will pay the unpaid balance of the interest if he can obtain terms “as shall make the sacrifice upon the exchange more tolerable.”

De Wolf is then reminded of his place in the pecking order; the United States will not grant him favors because he advanced “the remaining trifle until the arrival of the remittances.” Adams continues: “You cannot imagine that I shall accede to the reduced offer, when I did not think it proper to accept the larger one…founded upon engagements extorted by the supply at an accidental and unforeseen occasion your advances must assuredly be altogether optional.”

What upset Adams most was the letter in The Rotterdam Gazette because he knew that the information it contained was in essence correct. It probably reflected his worst nightmare but he could not admit that to an outsider like De Wolf. He concluded, “I have no doubt that the election of President and Vice-President have taken place without the least disturbance and that the ensuing President will enter upon his office in equal quiet.” In reality Adams wasn't officially informed of the result of the elections before late in March 1797: John Adams won, but his main opponent, Thomas Jefferson, not his running mate, was appointed Vice President.

De Wolf needed some time to recover from Adams’ stabs at him. But the latter was doing his utmost to speed up payment of the unpaid interest tranche. On January 26, 1797, De Wolf informed Adams that the Amsterdam Bankers had ordered him to draw a draft on them in Antwerp Courant money instead of Dutch guilders. Simplified, that meant that the problem of exchanging one currency for another has been solved and hence also the high transaction costs. That meant also that Willink & Staphorst had found a way to provide De Wolf with Brabantine guilders cash in Antwerp. For De Wolf that challenged fundamentally his understanding of banking; Willink and Staphorst had beaten him on his own turf, a very bitter pill to swallow.

The United States of America was again current on the payment of its Antwerp loan. Based on the letters sent to De Wolf by Treasury Secretary Wolcott on October 10, 1798 and July 6, 1799, there is evidence that the interest for these years was also paid at maturity. For the year 1802 there is circumstantial evidence that, thanks to the intervention of an American lawyer specializing in these matters, the interests were also paid.

In the course of January 1797, the relationship between Adams and De Wolf improved to some extent. De Wolf sent a detailed account statement that Adams returned signed and approved. De Wolf claimed payment of the balance of 3,000 guilders in his favor, but the account statement showed that the actual amount was 3,198 guilders. It was this amount that was actually paid on Adams’s instruction, which was very typical for Adams, who didn’t accept presents.

Mid-February 1797, Adams had still not been officially informed who had won the Presidential election, but in Europe the rumor circulated that John Adams was the victor. So, on February 16, 1797, De Wolf wrote: “I cannot forbear making you my most sincere compliments upon the election of your Worthy father as President of the Congress(sic) of the United States of America may the Lord conserve him for many years.” Like most Europeans, De Wolf didn’t understand the uniqueness of the American Presidency.

Adams prudent as always, reminded De Wolf that the news wasn’t official yet but nevertheless thanked him. Progressively the outlook of Adams’s private and professional life improved considerably. Until Adams’s official departure from the Netherlands, they exchanged information, and the tone in their letters was again cordial. But Adams’s tenure as U.S. envoy in The Hague was coming to an end.

12. Closure: Eternal glory for Adams in 1815

George Washington had already signed Adams's recall from The Hague in August 1796. Washington also signed his new appointment, as ambassador in Lisbon. Adams was succeeded in The Hague by his very good friend William Vans Murray (1760-1801). Adams married Louisa Catherine Johnson on July 26, 1797.

Before his departure for Lisbon, President John Adams changed his destination from Lisbon to Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia. From there on John Quincy Adams's career and personal life knew high points and low points, experiencing joy and grief. During his career as a diplomat, he had to live abroad on a tight budget, which proved challenging. The American diplomats were always invited by their colleagues, but those that had to function on the budget allocated by the State Department couldn't reciprocate the favor.

In June 1814 Adams was back in Antwerp, lodged at he “Hôtel du Grand Laboureur”, less than 100 yards from the De Wolf Bank. De Wolf had died in 1806. In 1814 the Bank was owned by his widow, Joan Antonia Ergo, who in 1810 had married Joseph Henry de Caters, a nobleman who managed the Bank on her behalf. Antwerp and Amsterdam were now located in the same country, the Kingdom of the United Netherlands. From Antwerp, Adams traveled to Ghent, where he stayed from late June 1814 to early 1815.

He was head of the delegation (Albert Galatin, Henry Clay and J.H. Bayard) ) that had to negotiate the Peace Treaty with Britain for the War of 1812. The British were not in a hurry, and there were extended periods when Adams and the others had spare time. The biggest event in Ghent was (and still is) the Flower Show, and the Americans were asked to participate in the contest. Adams was the only one who took this seriously. Adams regularly visited the plant nursery and had serious discussions with the head gardener/ banker Jean De Meulemeester. They decided to participate with two flowers in the contest. Adams almost won the first price. As evidenced by the original document that we found, Adams won the second price – “honorable mention” – with his “andromeda cassinifolia”. Eternal glory for Adams in the Great City of Ghent.

Today few people in Ghent know that Adams became the sixth President of the United States, but all professional gardeners know that the most beautiful Azalea Americana is called Columbia in honor of the American Peace Delegation of 1814. That Peace Treaty was signed on December 24, 1814.

But most importantly we can conclude that the American Government was of the opinion that their bondholders had to be treated fairly. In extraordinary circumstances they did their utmost to honor their debts in Antwerp as well as in Amsterdam. In that, they were rather unique in comparison to other borrowers.